Unraveling workplace dynamics: exploring the nexus of perceived narcissistic supervision, workplace bullying and employee responses: through the lens of conservation of resources theory

Al-Hamd Islamic University Islamabad

Tahira Nazir

COMSATS University Islamabad (WAH Campus)

Abstract. In this paper, we examine how narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying affect job wellbeing and employee silence through emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation in order to address gaps in recent research and highlight the effects of adverse working conditions on performance behaviors of employees. We conducted a pilot study involving data from 51 employees in the fast food industry and performed confirmatory factor analysis. We then collected data from 616 employees to assess the relationship between the study variables. Results indicate that perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying have a direct positive relationship with employee silence, and a negative relationship with job well-being behaviors. They also reveal significant indirect relationships between the variables and support our hypotheses. These insights contribute meaningfully to academic literature and have practical implications for organizations striving to address the challenges posed by negative work environments. We highlight limitations of the study and provide future recommendations to enable researchers to assess the generalizability of our results.

Keywords: Workplace bullying; perceived narcissistic supervision; emotional exhaustion; psychological contract violation; employee silence; job well-being.

DESENTRAÑANDO LA DINÁMICA LABORAL: EXPLORANDO EL NEXO ENTRE LA SUPERVISIÓN NARCISISTA PERCIBIDA, EL ACOSO EN EL LUGAR DE TRABAJO Y LAS RESPUESTAS DE LOS EMPLEADOS A TRAVÉS DEL ENFOQUE DE LA TEORÍA DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LOS RECURSOS

Resumen. En este artículo, analizamos cómo la supervisión narcisista y el acoso laboral afectan el bienestar laboral y el silencio organizacional de los empleados, a través del agotamiento emocional y la violación del contrato psicológico, con el fin de abordar vacíos en la investigación reciente y destacar los efectos de condiciones laborales adversas sobre los comportamientos de desempeño de los trabajadores. Realizamos un estudio piloto con datos de 51 empleados del sector de comida rápida y llevamos a cabo un análisis factorial confirmatorio. Posteriormente, recopilamos datos de 616 empleados para evaluar la relación entre las variables del estudio. Los resultados indican que la supervisión narcisista percibida y el acoso laboral tienen una relación directa positiva con el silencio organizacional, y una relación negativa con los comportamientos asociados al bienestar laboral. También revelan relaciones indirectas significativas entre las variables y respaldan nuestras hipótesis. Estos hallazgos aportan de manera significativa a la literatura académica y tienen implicaciones prácticas para las organizaciones que buscan enfrentar los desafíos de entornos laborales negativos. Se señalan las limitaciones del estudio y se ofrecen recomendaciones para investigaciones futuras, con el objetivo de evaluar la generalización de los resultados obtenidos.

Palabras clave: Acoso laboral; supervisión narcisista percibida; agotamiento emocional; violación del contrato psicológico; silencio del empleado; bienestar laboral.

1. Introduction

Perceived narcissistic supervision (Jahanzeb and Raja, 2024) and workplace bullying (Zheng et al., 2024) have garnered increased attention in recent studies due to their impact on employees’ behavior. Aggressive work environments and the dark personality traits of supervisors significantly influence employees’ work attitudes and social interactions (Diller et al., 2023). The supervisory style plays a crucial role in shaping organizational outcomes. Supervisors’ dark traits and egoistic behaviors foster perceptions of narcissism among subordinates (Gruda et al., 2022). Employees consistently evaluate their immediate supervisors, which in turn shapes their attitudes toward their work (Penning de Vries et al., 2022). Self-centered supervision has a detrimental effect on employee performance (Shoukry et al., 2024). The link between positive work outcomes and the relationship between supervisors and subordinates hinges on a supportive social work environment and the fulfillment of psychological contracts. When psychological contracts are not met, employees find it difficult to engage meaningfully in their work tasks (Tekleab et al., 2020).

Organizations invest considerable time and resources into creating a well-being environment and establishing policies to prevent uncivil behavior (Bijalwan et al., 2024). Job well-being behaviors are often influenced by narcissistic supervision (Diller et al., 2023). Employees who perceive high levels of narcissistic supervision undermine the well-being environment and resort to silence (Emelifeonwu and Valk, 2019). Supervisors who fail to recognize their subordinates’ emotions in stressful situations contribute to emotional exhaustion, while employees’ emotional responses in turn shape behavioral patterns. Moreover, well-being behaviors are negatively impacted by workplace bullying.

Workplace bullying fosters insecurity, low morale, depression, stress, withdrawal of voice, fear, disgust, and other negative emotions (Khan et al., 2021). These emotions create situations where employees are more likely to intentionally reduce their effort or even quit their tasks. When workplace bullying and injustice are present, well-being behaviors and social communication are less frequent. The social exclusion aspect of workplace bullying isolates individuals from work-related social relationships, causing them to withdraw and remain silent (Ren and Kim, 2023).

Recent studies have highlighted that perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying contribute to low job performance, negative emotions, employee silence, and violations of psychological contracts (Jahanzeb and Raja, 2024; Zheng et al., 2024; Diller et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2022). It is essential to examine how perceived narcissistic supervision affects employee interpersonal relationships, psychological contracts, and well-being behaviors, and to explore the mediating role of emotional exhaustion in employee silence and well-being behaviors (Zhong et al., 2022; Mell et al., 2022). Furthermore, the relationships between psychological contract violations, perceptions of narcissistic supervision, and the effects of workplace bullying on job well-being, employee interpersonal relationships, and psychological contract violations require further investigation (Ribeiro et al., 2024; Diller et al., 2023; Mirzaei and Aghighi, 2024). This study aims to extend recent research by Khan et al. (2021) and Khan et al. (2022), focusing on banking and telecommunications employees. We investigate the effects of perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying by incorporating additional variables to explore their impact on job performance behaviors and employee silence. Specifically, we use emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation as mediating variables and apply a robust analysis within the fast food chain industry in Pakistan.

2. Theoretical description & hypothetical development

We examined the literature and incorporated the well-established theoretical framework of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. According to this theory, individuals are unable to utilize valuable resources when faced with stressors (Hobfoll and Shirom, 2001). The theory posits that work conditions significantly affect employees’ job performance and commitment. Workers’ resources are vulnerable, and in environments marked by bullying and high stress, individuals are unable to preserve their existing resources. Workplace bullying and perceived self-centered behavior by supervisors lead to emotional exhaustion, reduced engagement, and diminished well-being. Under such conditions, individuals tend to avoid upward communication, choosing instead to remain silent. Valuable resources and psychological contracts are eroded by organizational unfairness.

In this study, we also employ Trait Activation Theory to examine the effects of perceived narcissistic supervision on employee silence and job-related well-being (Chen, Zhang, et al., 2024). We extend the literature on workplace bullying and narcissistic supervision by analyzing the effects of these two independent variables on employee silence and job well-being. Additionally, we contribute to the literature by exploring the mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation in the relationship between workplace bullying, perceived narcissistic supervision, employee silence, and job-related well-being.

2.1 Effects of perceived narcissistic supervision on job well-being behaviors and employee silence

Positive and negative supervisor roles manifest in organizations in various ways. Negative supervisory behaviors are closely linked to employee performance and well-being (Emmerling et al., 2023). The “dark triad” traits in supervisors—such as narcissism—have a detrimental impact on organizational well-being and harm interpersonal relationships (Diller et al., 2023). Employees are generally more sensitive to negative experiences than positive ones, meaning that a toxic work atmosphere tends to exert a stronger influence on their behavior. A narcissistic supervisor tends to reduce job satisfaction, performance, and well-being, while increasing workplace stress (Shoukry et al., 2024). Individual work behaviors related to well-being are negatively associated with narcissistic personality traits. For instance, subordinate motivation and performance have been negatively correlated with the perceived power of supervisors (Ribeiro et al., 2024). A supervisor perceived as narcissistic often leads employees to socially withdraw from one another. A culture of silence tends to emerge under narcissistic supervision, as employees remain quiet in anticipation of negative or hostile responses from listeners, or due to confrontational interactions with colleagues and supervisors (Pinder and Harlos, 2001). While motivated employees often go beyond their assigned tasks, those who perceive their supervisor as narcissistic—particularly in social interactions—tend to work with reduced energy. Employee silence is typically a reflection of unsupportive leadership and a weak feedback system (Botha and Steyn, 2023).

H1: Perceived narcissistic supervision will negatively influence job well-being behaviors and positively affect employee silence.

2.2 Perceived narcissistic supervision, psychological contracts violation and emotional exhaustion

An egocentric supervisory style, combined with a negative organizational culture and poor conflict management, undermines psychological contracts in the workplace. Many employees respond sensitively to psychological contracts shaped by leadership behavior (Emmerling et al., 2023). Those who feel betrayed by their organization often report high levels of job insecurity and reduced communication (Tekleab et al., 2020). Supervisory behavior has been positively associated with the violation of psychological contracts. These contracts are directly influenced by both the experience and perception of narcissistic supervision. Employees who perceive a high level of narcissism within the organization are more likely to disregard the formation of psychological contracts with supervisors and colleagues. Subordinates of narcissistic leaders often feel tense, emotionally exhausted, and depressed; they struggle to be productive and tend to avoid speaking up (Diller et al., 2023). Emotional exhaustion is a common consequence in such environments (Zeeshan et al., 2024). Perceived narcissistic supervision and its ripple effects pose a serious threat to an employee’s emotional and cognitive resources. Negative emotions are exacerbated by the perception of narcissistic leadership (Shina and Hur, 2020).

H1a: Perceived narcissistic supervision will be positively related to psychological contract violation and emotional exhaustion.

2.3 Relationship between psychological contract violations, emotional exhaustion, perceived narcissistic supervision, and job well-being behaviors

An employee’s level of performance is influenced by job insecurity, supervisor support, and well-being behaviors. Employees who experience violations of the psychological contract tend to be more disengaged and experience greater job insecurity (Wu et al., 2024). Supervisors are often perceived as representatives of the organization. Therefore, when supervisors exhibit abusive or self-centered behavior, employees may attribute these actions to the organization itself, leading to a perceived breach of the psychological contract. This dynamic can foster a non-collaborative atmosphere where colleagues are less inclined to support one another in completing work tasks (Pradhan et al., 2020).

Psychological contract violations are negatively correlated with perceptions of organizational justice. Employees’ perception of such violations increases when key elements of organizational justice (e.g., normative fairness) are not properly upheld. Those who perceive a higher degree of contract violation are more likely to withdraw from responsibilities and exhibit disengagement in their roles (Latorre et al., 2020).

H1b: Psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion will negatively mediate the relationship between perceived narcissistic supervision and job well-being behaviors.

2.4 Relationship between emotional exhaustion, psychological contract violations, perceived narcissistic supervision, and employee silence

Employees’ perceptions of a supervisor’s coercive or legitimate power can induce stress, weaken well-being behaviors, and reduce their commitment to work. Consequently, their motivation to perform effectively diminishes (Zeeshan et al., 2024). Heightened emotional exhaustion—manifested through feelings of anger, guilt, and other negative emotions—combined with perceptions of a supervisor’s entitled behavior, deteriorates the quality of the supervisor-subordinate relationship (Chen, Zhang, et al., 2024).

Emotional exhaustion mediates the impact of the work environment on job satisfaction and retention intentions. When employees feel they have less autonomy and weaker relationships with their supervisors, emotional exhaustion tends to increase. This, in turn, has been linked to higher turnover intentions. Narcissistic supervision disrupts perceived fairness in terms of autonomy, distributive justice, and procedural justice, thereby exacerbating emotional exhaustion (Knudsen et al., 2008).

Perceptions of narcissistic supervision—such as coercion and selfishness—undermine trust and contribute to an increase in employee silence. The degree of silence is often proportional to the intensity of the supervisor’s narcissistic behavior. Moreover, an employee’s willingness to voice concerns depends significantly on how receptive the supervisor is. Fair leadership tends to reduce silence, whereas perceived injustice amplifies it (Zill et al., 2018).

Psychological contracts are directly impacted by how employees experience and interpret supervisor narcissism. Individuals who perceive high levels of narcissism within their organization are more likely to remain silent due to feelings of betrayal and psychological contract violations. Such perceptions—particularly of abusive supervision—have also been associated with broader organizational factors, such as the perceived fairness of procedural justice (Welander et al., 2019).

H1c: Psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion will positively mediate the relationship between perceived narcissistic supervision and employee silence.

2.5 Effects of workplace bullying on job well-being behaviors and employee silence

Workplace bullying is defined as deviant, antisocial behavior in the work environment with the intent to harm individuals. Such behavior is often characterized by rudeness, discourtesy, and a disregard for social norms (Ren and Kim, 2023). Bullying in the workplace can have deeply distressing consequences for employee well-being, affecting both social and personal factors that influence outcomes like job satisfaction and commitment.

Job-related well-being is significantly shaped by the coping strategies employees adopt in response to negative experiences. When negative interactions persist among coworkers, they can transform a once-positive workplace culture into a hostile environment that consciously undermines others (Jung and Yoon, 2018). Workplace bullying has been linked to both employee engagement and disengagement, depending on how these behaviors develop within organizational contexts (Mirzaei and Aghighi, 2024).

Moreover, bullying contributes to a culture of silence, where employees refrain from voicing concerns or reporting mistreatment. Such behavior often stems from fear or learned helplessness within an abusive setting. Individuals tend to withhold knowledge and information, opting for silence as a coping mechanism in response to negative organizational practices (Morrison, 2014). In this sense, bullying behaviors actively foster environments where silence becomes the norm (Brinsfield, 2013).

H2: Workplace bullying will negatively influence job well-being behaviors and positively influence employee silence.

2.6 Workplace bullying, psychological contract violation, and emotional exhaustion

Over the past four decades, psychological contracts in the workplace have been significantly affected by the presence of severe bullying. Workplace bullying not only damages individual psychological contracts but also undermines the broader sense of organizational justice. Scholars have examined how bullying correlates with employees’ perceptions of fairness and psychological contract violations (Naseer and Raja, 2019).

Psychological contracts—unwritten expectations between employees and organizations—are essential for cultivating trust and commitment. However, negative workplace events, such as bullying, can trigger perceptions of interactional and distributive injustice (Khan et al., 2021). These violations may serve as mediating mechanisms in the relationship between deviant workplace behaviors and long-term organizational dysfunction.

Modern employees face various stressors, including high-pressure tasks, insecure employment conditions, and rapidly changing work environments. Persistent negative interactions can intensify stress, provoke anxiety, and reduce emotional engagement and performance (Ren and Kim, 2023). Additionally, workplace bullying has been associated with both physical and emotional harm (Ballard and Easteal, 2018). Environments where bullying occurs often lead to emotional exhaustion, as supported by evidence that such settings generate heightened levels of negative affect (Jung and Yoon, 2018; Danauskė et al., 2023).

H2a: Workplace bullying will be positively related to psychological contract violation and emotional exhaustion.

2.7 Relationship between psychological contract violation, emotional exhaustion, workplace bullying, and job well-being behaviors

Empirical studies have emphasized the mediating role of psychological contract violations in the relationship between well-being behaviors (such as work engagement) and workplace bullying. Psychological detachment has been found to intensify the impact of bullying on counterproductive work behaviors. The “dark side” of psychological contracts links the negative consequences of cynicism to deteriorations in well-being behaviors (Tong et al., 2020).

Job insecurity is positively correlated with workplace bullying and also mediates its effect on work performance (Shina and Hur, 2020). Psychological contract violations are exacerbated by the aftermath of workplace bullying, which tends to generate negative emotions that prompt employees to intentionally disengage from tasks or reduce their effort. Uncivil behaviors in the workplace often stem from overwhelming job demands, leading to emotional exhaustion. Over time, this exhaustion diminishes job satisfaction and contributes to chronic fatigue (Koon and Pun, 2018).

Fear induced by an insecure environment has been linked to emotional exhaustion through symptoms like anxiety, anger, and burnout (Lee et al., 2019). Nielsen and Einarsen (2012) demonstrated that emotional exhaustion plays a significant mediating role between workplace bullying and work performance. Similarly, Ren and Kim (2023) explored both direct and indirect effects of bullying on employees’ willingness to work, finding that bullying leads to greater emotional exhaustion and decreased motivation to complete tasks. Hur et al. (2016) further underscored the importance of emotional states, showing that negative emotions significantly reduce the quality of work when employees operate under emotional strain.

H2b: Psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion will negatively mediate the relationship between workplace bullying and job well-being behaviors.

2.8 Relationship between psychological contract violation, emotional exhaustion, workplace bullying, and employee silence

Substantial empirical evidence supports the idea that psychological contract fulfillment strongly influences employee performance. When psychological contracts are not upheld, employee well-being declines, along with discretionary efforts such as communication and active participation (Botha and Steyn, 2023). Although motivated employees often go beyond their assigned duties, perceptions of narcissistic supervision can drain their energy and reduce engagement (El-Naggar et al., 2023).

Psychological detachment has also been found to intensify the consequences of bullying, leading to counterproductive work behaviors (Tong et al., 2020). When psychological contracts are violated, employees are more likely to remain silent and refrain from reporting uncivil or inappropriate behavior. Burnout, emotional exhaustion, fear, and the threat of conflict often underlie this silence (Morrison, 2023).

Employees’ emotions serve as mediators between their engagement at work and exposure to bullying (Mirzaei and Aghighi, 2024). Hostile work environments give rise to negative emotions, which encourage disengagement or deliberate task neglect. Organizational stressors and interpersonal conflict can escalate frustration, leading to decreased performance (Olaleye and Lekunze, 2024). Bullies provoke psychological distress—manifested in stress, depression, and anxiety—which can also lead to social isolation (Einarsen et al., 2003).

Emotional exhaustion functions as a key mediator between uncivil workplace behaviors and poor job performance. Exhausted employees tend to withdraw from responsibilities, participate less in organizational life, and increasingly isolate themselves. Emotions such as regret, fear, shame, guilt, and anger further influence the degree to which employees are willing or able to express themselves (Einarsen et al., 2003).

H2c: Psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion will positively mediate the relationship between workplace bullying and employee silence.

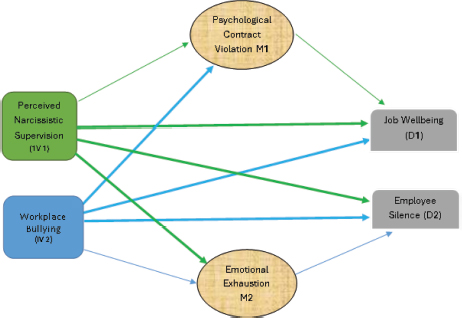

This figure illustrates that perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying are directly associated with employee silence and job wellbeing, and indirectly associated through psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework

3. Methodology

3.1 Research method and design

For this study, we adopted a quantitative approach and used a survey to examine the relationships between the key variables. A quantitative design is particularly useful for measuring individual attitudes, opinions, and behaviors (Pinquart and Schindler, 2007). We chose a cross-sectional research design, meaning that all variables were assessed at a single point in time. While this method may seem limited by its snapshot nature, it offers valuable insights, especially when considering specific time lags. Cross-sectional studies are often more practical and cost-effective compared to longitudinal designs, allowing us to capture important relationships between variables within a short timeframe (Pinquart and Schindler, 2007).

3.2 Population, data collection and sampling technique

Recent research in the banking and telecommunications sectors has highlighted a troubling trend: workplace bullying and the perception of narcissistic supervision appear to hinder employee performance (Khan et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2022). Building on these findings, the present study shifts the focus to a different but equally dynamic industry—fast food. Specifically, it explores how these negative workplace dynamics affect staff members employed at leading fast food chains, including Pizza Hut, McDonald’s, KFC, Burger King, Papa John’s, and Subway. The study targets branches located in several major cities: Lahore, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Mirpur, Gujrat, and Peshawar. Participants were selected from both regional and city-level outlets.

3.3 Data collection procedure

Branch managers were initially contacted, and upon receiving their consent, data collection commenced using both online Google Forms and printed questionnaires distributed during in-person visits. The survey was conducted in English, a language that participants reported understanding with ease. In the initial phase, responses were gathered from 51 employees as part of a pilot study aimed at testing the model. This phase also served to assess the suitability and reliability of the adopted scales, which were validated through confirmatory factor analysis.

Following this, data were collected from the main sample using the same questionnaire, with no modifications to its content or language. In the second phase, a total of 930 questionnaires were distributed. The study received 230 completed forms online and 396 via hard copies. After excluding 10 improperly filled responses, the final dataset comprised 616 valid samples for analysis.

3.4 Control variables

The study included age, gender, work experience, and academic qualifications as control variables (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic details

Description |

Number |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

Female |

202 |

32.8 |

Male |

414 |

67.2 |

|

Total |

616 |

100 |

|

Academic Qualification |

Intermediate |

138 |

22.4 |

Degree |

366 |

59.42 |

|

Master’s |

112 |

18.18 |

|

Total |

616 |

100 |

|

Age |

18-30 Years |

314 |

51.29 |

31-40 Years |

216 |

35.06 |

|

Above 40 Years |

86 |

13.65 |

|

Total |

616 |

100 |

|

Work Experience |

Less than 1 Year |

102 |

16.55 |

1-10 Years |

332 |

53.89 |

|

10-15 Years |

128 |

20.77 |

|

More than 15 Years |

54 |

8.79 |

|

Total |

616 |

100 |

3.5 Instrument justification

This study employed several standardized questionnaires originally developed by Western researchers and written in English. These instruments were carefully reviewed by the research team and their academic supervisor, all of whom possess expertise in business studies and practical experience within organizational settings. After a subjective evaluation, the instruments were deemed appropriate for the target population. Since all items were contextually relevant, no cultural adaptation was necessary.

The choice to use English-language instruments was also deliberate. The study’s participants were highly qualified professionals, many of whom operate in environments where English functions as the official language of communication. To reinforce this assumption, a pilot study was conducted with a smaller subset of participants. The results confirmed that both the language and content of the questionnaires were well-suited to the broader sample.

Notably, these instruments have been successfully applied in prior studies involving Asian populations, including those from Pakistan. Their established validity across cultural contexts served as further justification for their adoption in this research, particularly given their prior use in studies from the banking and telecommunications sectors. While the development of indigenous tools might offer deeper cultural resonance, such an endeavor often proves time-intensive and redundant when reliable scales are already available. In the current study, additional efforts were made to validate the instruments and ensure alignment with local cultural norms.

3.6 Instruments and measurements

Participants were asked to assess perceived narcissistic supervision using a six-item scale developed by Hochwarter and Thompson (2012). Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), with the scale demonstrating a reliability coefficient of 0.87.

To evaluate workplace bullying, the study used the 22-item Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) by Einarsen et al. (2009), which addresses three dimensions: work-related, person-related, and physical intimidation. Participants rated each item on a five-point frequency scale from “never” (1) to “always” (5). This scale showed high internal consistency, with a reliability of 0.95.

Psychological contract violations (PCV) were measured through a four-item scale developed by Robinson and Morrison (2000), again using a five-point Likert format (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with a reliability score of 0.86.

Emotional exhaustion was assessed using the six-item subscale from Maslach and Jackson’s (1981) inventory. Although the text erroneously notes a Likert scale from 1 to 2, the intended format appears to be the standard five-point agreement scale. This measure achieved a reliability of 0.88.

Employee silence was measured via Brinsfield’s (2013) scale, also based on a five-point agreement spectrum. It yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.90.

Finally, job well-being was evaluated using a 17-item instrument developed by Schaufeli et al. (2006), which utilizes a six-point frequency scale ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (6). This scale demonstrated strong reliability at 0.92.

4. Results and analysis

4.1 Analytical strategy

The present study analyzed the collected data in three phases. In the first phase, the model was tested and CFA was carried out using SPSS 2.8 and AMOS software version 26. In the second phase, convergent and discriminant validity and outer model assessment were performed using PLS-SEM on SMART-PLS version 4.0.2. In the final mediation-moderation analysis phase, direct and indirect relationships were examined using a PROCESS macro model proposed by Hayes (2013).

After the initial analysis with SPSS, model fit indices were observed based on six factors established in a rotated component matrix, i.e., perceived narcissistic supervision, workplace bullying, emotional exhaustion, psychological contract violation, employee silence, and job well-being behaviors. AMOS software was then used to calculate model fit indices. The values of CMIN/DF ranged from 4 to 6.27, and GFI values were close to 0.90, which are considered fair (Kline, 2011). RMSEA values ranged from 0.05 to 0.10, which are satisfactory (p < 0.045) (Hair et al., 2019; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Table 2 shows the goodness-of-fit indicators. The values of CMIN/DF are 2.083, GFI 0.922, SRMR 0.100, and RMSEA 0.07. These model fit values indicate a significant level and provide a suitable basis for further analysis.

Table 2. Model fit indices

Communalities of Constructs |

Measure |

Estimate |

Threshold |

Interpretation |

CMIN |

4711.129 |

-- |

-- |

|

PNS: 0.739 |

DF |

2262 |

-- |

-- |

WB: 0.667 |

CMIN/DF |

2.083 |

Between 1 and 3 |

Excellent |

EE: 0.724 |

CFI |

0.922 |

>0.95 |

Acceptable |

ES:0.684 |

SRMR |

0.1 |

<0.08 |

Acceptable |

PCV:0.734 |

RMSEA |

0.07 |

<0.06 |

Acceptable |

JWB:0.979 |

PClose |

0 |

>0.05 |

------ |

Notes: PNS= perceived narcissistic supervision; WB=workplace bullying; EE=emotional exhaustion; ES=employee silence; PCV=psychological contract violation; JWB=job well-being behaviors; CFI=comparative fit index; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; SRMR= standardized root mean residual

Table 2 presents the communality of each item after conducting the CFA in SPSS. The communalities of each construct are also satisfactory. These results demonstrate the significance and relevance of each item to the present study. There were no issues regarding the usability of the research questionnaires, as the respondents were well-informed and well-educated.

4.2 Assessment of the measurement model

The hypotheses and the statistically significant differences among the variables were tested using PLS-SEM (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling). The analysis was performed using Smart PLS 4.1.0.0 software. The data from this study were initially processed using the PLS algorithm to assess outer loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability, discriminant validity, and the variance inflation factor (VIF). Items with loadings greater than 0.70 indicate that the model explains over 50% of the variance in the constructs. Cronbach’s alpha should not be used; instead, composite reliability should be greater than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019). Table 3 presents the item loadings for each variable. All item loadings were greater than 0.60, demonstrating the model’s relevance. The values of composite reliability should exceed 0.60, although in established research they should ideally be above 0.70. As a rule, exploratory research with a minimum reliability of 0.60 in the model is acceptable (Hair et al., 2019).

Table 3. Measurement of outer model

Constructs |

Indicators |

Loadings |

VIF |

Constructs |

Indicators |

Loadings |

VIF |

Workplace Bullying |

WB 1 |

0.633 |

1.758 |

ES 4 |

0.778 |

2.233 |

|

WB 2 |

0.62 |

1.802 |

ES 5 |

0.778 |

2.123 |

||

WB 3 |

0.66 |

1.731 |

ES 6 |

0.671 |

1.596 |

||

WB 6 |

0.648 |

1.928 |

ES 10 |

0.661 |

1.976 |

||

WB 7 |

0.664 |

1.842 |

ES 11 |

0.713 |

2.138 |

||

WB 8 |

0.779 |

2.745 |

ES 12 |

0.647 |

1.944 |

||

WB 9 |

0.723 |

2.162 |

ES 13 |

0.714 |

2.079 |

||

WB 10 |

0.663 |

2.671 |

Perceived Narcissistic Supervision |

PNS 1 |

0.755 |

1.851 |

|

WB 11 |

0.731 |

2.837 |

PNS 2 |

0.745 |

1.764 |

||

WB 12 |

0.773 |

2.737 |

PNS 3 |

0.785 |

1.764 |

||

WB 13 |

0.768 |

2.671 |

PNS 4 |

0.739 |

1.595 |

||

WB 14 |

0.711 |

2.125 |

PNS 5 |

0.656 |

1.445 |

||

WB 15 |

0.75 |

2.912 |

PNS 6 |

0.698 |

1.473 |

||

WB 16 |

0.701 |

3.279 |

Psychological Contract Violation |

PCV 1 |

0.779 |

1.505 |

|

WB 17 |

0.715 |

2.764 |

PCV 2 |

0.792 |

1.616 |

||

WB 18 |

0.772 |

2.422 |

PCV 3 |

0.803 |

1.669 |

||

WB 19 |

0.761 |

1.741 |

PCV 4 |

0.762 |

1.526 |

||

WB 20 |

0.767 |

3.136 |

Job Well-Being |

JWB 2 |

0.691 |

1.751 |

|

WB 21 |

0.751 |

2.645 |

JWB 3 |

0.707 |

1.723 |

||

WB 22 |

0.731 |

2.165 |

JWB 4 |

0.692 |

2.187 |

||

Emotional Exhaustion |

EE 1 |

0.72 |

1.548 |

JWB 5 |

0.679 |

2.022 |

|

EE 2 |

0.717 |

1.521 |

JWB 7 |

0.678 |

1.869 |

||

EE 3 |

0.792 |

1.915 |

JWB 8 |

0.747 |

1.643 |

||

EE 4 |

0.742 |

1.677 |

JWB 9 |

0.652 |

2.019 |

||

EE 5 |

0.758 |

1.644 |

JWB 10 |

0.836 |

1.976 |

||

EE 6 |

0.76 |

1.697 |

JWB 11 |

0.662 |

2.138 |

||

Employee Silence |

ES 1 |

0.74 |

2.019 |

JWB 12 |

0.768 |

1.944 |

|

ES 2 |

0.741 |

2.053 |

JWB 15 |

0.828 |

2.079 |

||

ES 3 |

0.807 |

2.528 |

JWB 17 |

0.762 |

2.528 |

Before assessing the structural model, it is essential to determine the VIF (variance inflation factor), which is used to assess collinearity issues among the indicators. VIF values equal to or above 5 indicate collinearity problems (Wong, 2013), while ideally, they should be closer to 3 (Becker et al., 2015). Table 3 shows that all VIF values were below 5, indicating that there were no collinearity issues in the data. Additionally, Table 3 shows the composite reliability values, which reflect the significance level of composite reliability in this study.

The matrix used to evaluate convergent validity is the average variance extracted (AVE), calculated by computing the mean values and squaring the loading of each construct. AVE requires the loadings to be squared, and the mean of each construct to be computed. AVE should represent at least 50% of the item variance or be equal to or greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2019). Table 3 presents the average variance extracted (AVE) for all variables. All values were within the significant and relevant range for the current model.

The next step was to determine discriminant validity, which represents the distinctiveness of each construct from the others. Discriminant validity ensures that constructs are empirically different from one another. Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested using a traditional matrix to compare inter-construct correlations with the AVE of the same scale, and these correlations must be higher than 0.50. Table 4 shows the discriminant validity for perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying, where the higher diagonal values for all constructs are greater than the values below them, indicating the effective level of discriminant validity in the data.

Table 4. Convergent & discriminant validity

Constructs |

AVE |

CR |

EE |

ES |

JWB |

PNS |

PCV |

WB |

EE |

0.561 |

0.884 |

0.749 |

|||||

ES |

0.506 |

0.901 |

0.616 |

0.722 |

||||

JWB |

0.512 |

0.926 |

0.417 |

5.187 |

0.716 |

|||

PNS |

0.534 |

0.873 |

0.345 |

0.404 |

0.526 |

0.701 |

||

PCV |

0.615 |

0.865 |

0.221 |

0.401 |

0.199 |

0.447 |

0.684 |

|

WB |

0.51 |

0.955 |

0.031 |

0.209 |

0.168 |

0.422 |

0.513 |

0.518 |

EE=Emotional Exhaustion, ES=Employee Silence, WB=Well-being, PNS=Perceived narcissistic supervision, PCV=Psychological contract violation, WB=Workplace bullying, CR=Composite Reliability, AVE=Average variance extracted, DV=Discriminant validity by Fornell and Larcker 1981 criteria

4.3 Testing of hypotheses

The structural model was assessed in accordance with the recommendations by Hayes (2013) regarding the model criteria, which included the beta coefficients, corresponding p-values, and bootstrapping resampling of 5000 iterations using SMARTPLS 4.0.2. Bootstrapping was employed to assess significance by providing confidence intervals. P-values should be below 5%, and t-statistics should exceed 1.96. Positive path coefficient values indicate a direct relationship between the variables in the study, while negative values suggest an inverse relationship. The path coefficients meet the criteria set by the research questions, and all hypotheses were successfully tested. Workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision have a significant positive relationship with employee silence and a negative relationship with job well-being behaviors. Furthermore, emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation significantly mediated the relationships between the independent and dependent variables.

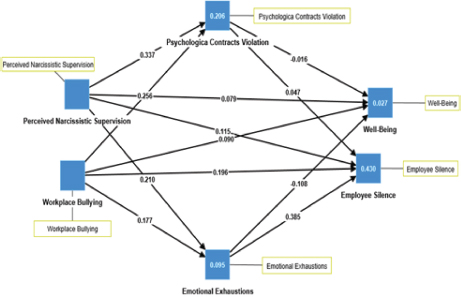

Figure 2 illustrates that perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying have direct associations with employee silence and job well-being, thereby confirming the direct hypotheses. These variables were also indirectly connected through the intervening role of psychological contract violations and emotional exhaustion.

Figure 2. Hypothetical relations

Path analysis describes the direct impact of the independent variables on the dependent variables, as well as the indirect mediation links hypothesized in the theoretical model used in this study. Table 5 shows the direct relationships between the independent variables and the dependent variables, as well as the mediator variables. Perceived narcissistic supervision has a direct positive relationship with employee silence but is not significantly associated with job well-being. On the other hand, PNS has a direct positive impact on emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation. Secondly, workplace bullying worsens job well-being and increases employee silence. Bullying behavior is also positively correlated with emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violations. Table 5 also shows that the T statistic reaches the level of significance, i.e., values are greater than 1.96, with p-values less than 0.05. This supports the seven hypotheses regarding the independent variables of perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying in relation to the mediator and dependent variables.

Table 5. Testing of the hypotheses with perceived narcissistic supervision

Hypotheses |

Independent Variables |

Mediators |

Dependent Variables |

β |

T values |

P Values |

Decision |

H1 |

PNS |

JWB |

0.079 |

1.051 |

0.294 |

Rejected |

|

H1 |

PNS |

ES |

0.115 |

2.68 |

0.008 |

Accepted |

|

H1a |

PNS |

PCV |

0.337 |

14.417 |

0.0000 |

Accepted |

|

H1a |

PNS |

EE |

0.21 |

4.47 |

0.0000 |

Accepted |

|

H1b |

PNS |

PCV |

JWB |

-0.016 |

1.995 |

0.001 |

Accepted |

H1b |

PNS |

EE |

JWB |

-0.219 |

4.071 |

0.004 |

Accepted |

H1c |

PNS |

PCV |

ES |

0.139 |

2.312 |

0.021 |

Accepted |

H1c |

PNS |

EE |

ES |

0.481 |

10.428 |

0.0000 |

Accepted |

EE=Emotional Exhaustion, ES=Employee Silence, WB=Well-being, PNS=Perceived narcissistic supervision, PCV=Psychological contract violation, WB=Workplace bullying; T value > 1.96, p vale <0.05

Table 6 shows that the T statistic reaches the level of significance, i.e., values are greater than 1.96, with p-values less than 0.05. This supports all eight indirect hypotheses involving the independent variables of workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision through the mediating variables of emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation. These results indicate that emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation significantly mediate the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Table 6. Testing of the hypotheses with workplace bullying

Hypotheses |

Independent Variables |

Mediators |

Dependent Variables |

β |

T values |

P Values |

Decision |

H2 |

WB |

JWB |

-0.011 |

2.228 |

0.043 |

Accepted |

|

H2 |

WB |

ES |

0.196 |

2.305 |

0.022 |

Accepted |

|

H2a |

WB |

PCV |

0.256 |

13.131 |

0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H2a |

WB |

EE |

0.177 |

5.133 |

0 |

Accepted |

|

H2b |

WB |

PCV |

JWB |

-0.061 |

2.252 |

0.025 |

Accepted |

H2b |

WB |

EE |

JWB |

-0.108 |

4.077 |

0 |

Accepted |

H2c |

WB |

PCV |

ES |

0.012 |

2.256 |

0.025 |

Accepted |

H2c |

WB |

EE |

ES |

0.385 |

10.179 |

0 |

Accepted |

EE=Emotional Exhaustions, ES=Employee Silence, WB=Well-being, PNS=Perceived narcissistic supervision, PCV=Psychological contracts violation, WB=Workplace bullying, T value > 1.96, p vale <0.05

5. Discussion

The present study utilized the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory to investigate the effects of workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision on employee silence and job well-being behaviors through the mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation. Our results confirm that perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying lead to a decrease in employees’ job resources, positive emotions, job well-being behaviors, and participation in work tasks. Job resources may include competence, self-efficacy, skills, and reputation, among others. Employees who feel betrayed develop negative perceptions of their organization. Professional growth becomes unfeasible when job resources are depleted. The main contribution of this study to the COR theory literature is that it demonstrates how adverse working conditions diminish existing job resources.

Drawing on COR theory, this study associates employee job resources with negative work environments, such as workplace bullying. Bullying increases the likelihood of resource loss. The loss of job resources resulting from psychological contract violation reduces well-being and discourages employees from putting forth adequate effort in the workplace (Hobfoll and Shirom, 2001). Employee reactions to bullying are accompanied by a depletion of current resources. Well-being behaviors—commonly regarded as valued resources—are undermined when employees fail to conserve their resources in resource-draining contexts such as bullying (Rosen et al., 2016; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Based on the COR theoretical framework, the present study confirms a direct relationship between workplace bullying and both employee well-being and silence. It also affirms that emotional exhaustion and psychological contract violation mediate the effects of workplace bullying on these outcomes, and that employee job resources continue to decline under such conditions.

The participants in this study were employees in Pakistan’s fast food industry. Several prior studies have identified factors that reduce employees’ work outcomes, voice, and well-being behaviors, including perceived narcissistic supervision (Zhong et al., 2022) and workplace bullying (Gruda et al., 2022). Perceived narcissistic supervision generates counterproductive work behaviors and suppresses well-being behaviors (Mell et al., 2022; Khan and Gul, 2022). Over the past three decades, workplace bullying has emerged as a social concern due to its pervasive and harmful impacts. Globally, workplace mistreatment—such as aggression, social undermining, and deviant behaviors—hampers individual and overall organizational performance. Employees’ mood, intentions, and well-being are shaped by their perception of the work environment (Bijalwan et al., 2024). Their reactions to incivility often manifest as negative emotions, including fear, anger, sadness, frustration, and helplessness. Employees’ day-to-day behaviors are driven by their emotions, and their emotional reactions and affective commitment tend to diminish in response to perceived psychological contract violations (Olaleye and Lekunze, 2024).

5.1 Implications for organizations

Employees face numerous negative workplace factors, such as harassment, threats, and insulting or self-centered behaviors. Perceptions of supervisor narcissism affect subordinates’ personalities and work performance. A second implication of this study is that employees often encounter bullying in the workplace. Training programs can help improve environments prone to such behavior. This study also provides insight into how organizational management and supervision can enhance their approach to negative workplace dynamics.

Our results offer guidance for managers and supervisors on addressing perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying. These leaders play a key role in shaping employee behavior and enhancing performance. Since employees interact with their supervisors daily, effective communication is more likely when emotional considerations are acknowledged. Organizations should actively address these issues by raising awareness through official meetings and both social and print media.

Creating a positive work environment that fosters emotional well-being and supportive behaviors is essential. Narcissistic tendencies among supervisors must be discouraged to prevent their detrimental effects on employee performance. Organizations should offer robust support systems and implement clear policies to promote well-being, counteract bullying, deliver relevant training, and ensure open upward communication (Srivastava et al., 2022). Fair treatment can also be ensured through effective performance appraisal systems that continuously evaluate employee contributions.

Finally, establishing open communication channels for employee feedback is crucial. These measures can reduce workplace silence and encourage expression. Freedom of expression plays a central role in preventing negative emotions and fostering strong psychological contracts. Without it, employees are more likely to withhold their opinions and disengage from organizational activities.

5.2 Limitations and recommendations for future research

This study presents several limitations. First, we employed a cross-sectional research design and tested the hypotheses within a specific timeframe. Future research could utilize a longitudinal design to explore the effects of workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision over different time intervals (Jahanzeb and Raja, 2024). A two- or three-wave longitudinal study would enable researchers to better understand the consequences of workplace bullying within culturally diverse organizational contexts.

Second, the sample used in this study was drawn from specific organizations in the fast-food industry. Future studies could extend the research to include different sectors and companies located in major cities across Pakistan. For instance, Zheng et al. (2024) suggest that the implications of workplace bullying should be analyzed across both generalized and culturally varied organizational settings.

Third, this study examined the effects of perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying on employee silence and job-related wellbeing, primarily from the employees’ or subordinates’ perspectives. Future research could investigate the dyadic relationships between supervisors and subordinates to derive more performance-oriented outcomes.

Fourth, we relied on previously developed quantitative measures to assess the model variables. Subsequent studies could introduce new scales or adopt qualitative methods for deeper exploration. Qualitative approaches such as diary studies could offer insights into the evolving nature of workplace bullying and its impact on victims’ responses and perceptions.

Fifth, future research could integrate additional variables into the current framework. A supportive and positive supervisory role has the potential to reduce negative emotions and enhance job wellbeing behaviors (Khan et al., 2022). Individual psychological evaluations within organizational settings should also be considered. Researchers may examine further mediating variables in the relationship between workplace bullying and wellbeing—such as affective commitment, psychological contract breaches, psychological distress, and self-efficacy—as well as in the link between workplace bullying and employee silence, including factors like organizational identification and interpersonal trust.

5.3 Conclusion

Within the framework of the Conservation of Resources theory applied to the fast-food industry in Pakistan, the findings from this study support the hypotheses that employees and subordinates are affected by perceived narcissistic supervision and bullying environments, which increase employee silence and reduce job wellbeing behaviors and valuable employee resources. This research highlights these negative consequences and provides solutions for overcoming bullying behaviors and perceived narcissistic supervision. Workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision often stem from the absence of policies, procedures, and communication for solving these problems. This paper, therefore, provides a possible solution for overcoming these organizational issues. The participants in this study were from major fast-food chains in several cities in Pakistan. Our study thus provides a gateway for future researchers to examine the effects of workplace bullying and perceived narcissistic supervision on employee silence and job wellbeing behaviors in other sectors and industries.

References

Ballard, A. J., & Easteal, P. (2018). The Secret Silent Spaces of Workplace Violence: Focus on Bullying (and Harassment). Laws, 7(4), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7040035

Becker, JM., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Völkner, F. (2015). How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Mark Lett 26, 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9299-9

Bijalwan, P., Gupta, A., Johri, A., & Asif, M. (2024). The mediating role of workplace incivility on the relationship between organizational culture and employee productivity: A systematic review. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2382894. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2382894

Botha, L., & Steyn, R. (2023). Employee voice as a behavioural response to psychological contract breach: The moderating effect of leadership style. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2174181

Brinsfield, C. T. (2013). Employee silence motives: Investigation of dimensionality and development of measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(5), 671–697.

Chen, G., Wang, J., Huang, Q., Sang, L., Yan, J., Chen, R., & Ding, H. (2024). Social support, psychological capital, multidimensional job burnout, and turnover intention of primary medical staff: A path analysis drawing on conservation of resources theory. Human Resources for Health, 22(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-024-00915-y

Chen, H., Zhang, L., Wang, L., Bao, J., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Multifaceted leaders: The double-edged sword effect of narcissistic leadership on employees’ work behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1266998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1266998

Danauskė, E., Raišienė, A. G., & Korsakienė, R. (2023). Coping with burnout? Measuring the links between workplace conflicts, work-related stress, and burnout. Business: Theory and Practice, 24(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2023.16953

Diller, S., Czibor, A., Weber, M., Klackl, J., & Jonas, E. (2023). Like moths into the fire: How dark triad leaders can be both threatening and fascinating. Research Square; 2023. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2528438/v1

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. (Eds.). (2003). Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203164662

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress, 23(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370902815673

El-Naggar, S. S. M., Soliman, M. G., & Elsetouhi, A. M. (2023). The Impact of Leader’s Dark Triad Personality Traits on Employee Career Growth: An Empirical Study on Mansoura University Employees. Scientific Journal for Financial and Commercial Studies and Research, 4(1), 407-423. https://doi.org/10.21608/CFDJ.2023.258049

Emelifeonwu, J.C. and Valk, R. (2019). Employee voice and silence in multinational corporations in the mobile telecommunications industry in Nigeria. Employee Relations, 41(1), pp. 228-252. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2017-0073

Emmerling, F., Peus, C., & Lobbestael, J. (2023). The hot and the cold in destructive leadership: Modeling the role of arousal in explaining leader antecedents and follower consequences of abusive supervision versus exploitative leadership. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(3), 237-278. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866231153098

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gruda, D., Karanatsiou, D., Hanges, P., Golbeck, J., & Vakali, A. (2022). Don’t go chasing narcissists: A relational-based and multiverse perspective on leader narcissism and follower engagement using a machine learning approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221094976

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Harms, P. D., Bai, Y., Han, G. H., & Cheng, S. (2022). Narcissism and tradition: How competing needs result in more conflict, greater exhaustion, and lower performance. International Journal of Conflict Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-11-2021-0219

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychological science, 24(10), 1918-1927.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 57–80). Marcel Dekker.

Hochwarter, W. A., & Thompson, K. W. (2012). Mirror, mirror on my boss’s wall: Engaged enactment’s moderating role on the relationship between perceived narcissistic supervision and work outcomes. Human Relations, 65(3), 335–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711430003

Hur, W. M., Moon, T., & Jun, J. K. (2016). The effect of workplace incivility on service employee creativity: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(3), 302-315. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2014-0342

Jahanzeb, S., & Raja, U. (2024). Does ethical climate overcome the effect of supervisor narcissism on employee creativity? Applied Psychology, 73(3), 1287–1308.

Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2018). Improving frontline service employees' innovative behavior using conflict management in the hospitality industry: The mediating role of engagement. Tourism Management, 69, 498-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.035

Khan, K., & Gul, M. (2022). The Role of Soft Skills and Organizational Unfairness between Leadership Style and Employee Performance: A Quantitative Study in Educational Institutes of Pakistan. IRASD Journal of Management, 4(4), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.52131/jom.2022.0404.0097

Khan, K., Nazir, T., & Shafi, K. (2021). The effects of perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying on employee silence: The mediating role of psychological contracts violation. Business & Economic Review, 13(2), 87–110.

Khan, K., Nazir, T., & Shafi, K. (2022). Measurement of job wellbeing behaviors by perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, 12(1).

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Knudsen, H.K., Ducharme, L.J., & Roman P.M. (2008). Clinical supervision, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: a study of substance abuse treatment counselors in the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. J Subst Abuse Treat, 35(4), 387-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.02.003

Koon, V.-Y., & Pun, P.-Y. (2018). The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction on the Relationship Between Job Demands and Instigated Workplace Incivility. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 54(2), 187-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886317749163

Latorre, F., Ramos, J., Gracia, F. J., & Tomás, I. (2020). How high-commitment HRM relates to PC violation and outcomes: The mediating role of supervisor support and PC fulfilment at individual and organizational levels. European Management Journal, 38(3), 462–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.12.003

Lee, M., & Jang, K.-S. (2019). Nurses’ emotions, emotion regulation and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 27(3), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-06-2018-1452

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113.

Mell, J. N., Quintane, E., Hirst, G., & Carnegie, A. (2022). Protecting their turf: When and why supervisors undermine employee boundary spanning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(6), 1009–1024.

Mirzaei, V., & Aghighi, A. A. (2024). Investigating the relationship between narcissistic leadership and organizational cynicism: The mediating role of employees' silence and negative rumors in the workplace. Psychological Researches in Management, 10(1), 33–67.

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

Morrison, E. W. (2023). Employee voice and silence: Taking stock a decade later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 79–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-054654

Naseer, S., & Raja, U. (2019). Why does workplace bullying affect victims’ job strain? Perceived organizational support and emotional dissonance as resource depletion mechanisms. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00375-x

Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 26(4), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.734709

Olaleye, B. R., & Lekunze, J. N. (2024). Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience on workplace bullying and employee performance: A moderated-mediation perspective. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 12(1), e2159.

Penning de Vries, J., Knies, E., & Leisink, P. (2022). Shared perceptions of supervisor support: What processes make supervisors and employees see eye to eye? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 42(1), 88–112.

Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 20, pp. 331–369). Emerald Group Publishing.

Pinquart, M., & Schindler, I. (2007). Changes of life satisfaction in the transition to retirement: A latent-class approach. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 442–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.442

Pradhan, S., Srivastava, A. and Mishra, D.K. (2020). Abusive supervision and knowledge hiding: the mediating role of psychological contract violation and supervisor directed aggression. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(2), pp. 216-234. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2019-0248

Ren, L., & Kim, H. (2023). Serial multiple mediation of psychological empowerment and job burnout in the relationship between workplace bullying and turnover intention among Chinese novice nurses. Nursing Open, 10, 3687–3695. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1621

Ribeiro, N., Gomes, D., Gomes, G. P., Ullah, A., Dias Semedo, A. S., & Singh, S. (2024). Workplace bullying, burnout and turnover intentions among Portuguese employees. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-11-2023-4259

Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(5), 525–546.

Rosen, C. C., Koopman, J., Gabriel, A. S., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(11), 1620–1634. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000140

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701-716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Shina, Y., & Hur, W. M. (2020). Supervisor incivility and employee job performance: The mediating roles of job insecurity and amotivation. The Journal of Psychology, 154(1), 38–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2019.1645634

Shoukry, D. E. E., El-Halem, A., Ghaith, A., & El-Saied Mortada, E. S. N. (2024). The effect of toxic leadership on tourism and hotel firm employee performance: The mediating role of job frustration. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 26(1), 386–410.

Srivastava, S., Mendiratta, A., Pankaj, P., Misra, R. and Mendiratta, R. (2022). Happiness at work through spiritual leadership: a self-determination perspective, Employee Relations, 44 (4), 972-992. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2021-0342

Tekleab, A. G., Laulié, L., De Vos, A., De Jong, J. P., & Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. (2020). Contextualizing psychological contracts research: A multi-sample study of shared individual psychological contract fulfilment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(2), 279–293.

Tong, J., Chong, S. H., Chen, J., Johnson, R. E., & Ren, X. (2020). The interplay of low identification, psychological detachment, and cynicism for predicting counterproductive work behaviour. Applied Psychology, 69(1), 59–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12187

Welander, J., Astvik, W., & Isaksson, K. (2019). Exit, silence and loyalty in the Swedish social services – the importance of openness. Nordic Social Work Research, 9(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2018.1489884

Wong, K. K.-K. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24, Technical Note 1.

Wu, H., Subramaniam, A., & Rahamat, S. (2024, April). The role of psychological contract breach and leader–member exchange quality in Machiavellianism and organisational cynicism. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship.

Zeeshan, M., Batool, N., Raza, M. A., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2024). Workplace ostracism and instigated workplace incivility: A moderated mediation model of narcissism and negative emotions. Public Organization Review, 24(1), 53–73.

Zheng, C., Nauman, S., & Jahangir, N. U. (2024). Workplace bullying and job outcomes: Intersectional effects of gender and culture. International Journal of Manpower. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-04-2023-0189

Zhong, R., Lian, H., Hershcovis, M. S., & Robinson, S. L. (2022). Mitigating or magnifying the harmful influence of workplace aggression: An integrative review. Academy of Management Annals, 16(1), 271–308.

Zill, A., Knoll, M., Cook, A. (Sasha), & Meyer, B. (2018). When Do Followers Compensate for Leader Silence? The Motivating Role of Leader Injustice. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(1), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818820861 (Original work published 2020)